|

| Inscription of Esarhaddon |

Also, please bear in mind that I am not a professional historian of the period. There are certainly mistakes and errors in the sources and I may make mistakes in my interpretations of these sources. Mistakes are particularly likely to occur when dealing with years, as the Babylonian/Assyrian/Jewish years do not correspond exactly to our own. So, there is the possibility that I may have interpreted an event as happening in late 670 when it may in fact have been early 669. If the reader spots any errors such as this, please let me know in the comments and I will research it and correct it as soon as possible.

|

| Assyrian soldier at a siege |

Elsewhere in the world, King Hui of the Eastern Zhou was the nominal emperor of the rapidly fading Zhou Dynasty, which was descending into feudal anarchy. The Greek states were transitioning from monarchies to tyrannies and were fighting the Lelantine and Second Messenian Wars. India was in the Later Vedic Period and the states such as Kuru, Panchala, Kosala and Videha were flourishing along the Ganges Plain. There were many other civilisations and cultures active at this time, but this will give the reader some idea of what is happening elsewhere in the world.

In 675 Nabu-ahhe-iddin was the Limmu, meaning the official who presided over the New Year’s ceremonies and who the year was named after, of Assyria. We see the Assyrian armies return to the troublesome north-western frontier to unsuccessfully besiege the rebellious state of Melid (or Malatya as it is now known). The Elamites under Humban-Haltas II attacked Sippar in southern Mesopotamia, ending the period of peace between Assyria and Elam. Their attack was unsuccessful however and they succeeded mainly in disrupting the religious ceremonies of the sun-god Shamash, whose great shrine was located in Sippar. The Elamite attack was short-lived. Humban-Haltas II was stricken with a mysterious illness that left him suddenly dead; the third Elamite king in succession to die suddenly of an unknown and unexpected illness. There must certainly have been some genetic anomaly in the Elamite royal family at this time.

|

| Inscription of Esarhaddon |

The king of Elam entered Sippar and a massacre took place. Shamash did not come out of Ebabbar. The Assyrian marched to Milidu. On the seventh day of the month Ulûlu, Humban-Haltas, king of Elam, without becoming ill, died in his palace. For five years, Humban-Haltas ruled Elam. Urtak, his brother, ascended the throne in Elam.

Babylonian Chronicles: From Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin

The Elamites were in no real condition to challenge the Assyrians again and the Assyrians were fighting a number of wars on the northern frontiers against the loose confederations of the Median/Cimmerian/Scythian tribes. In these wars it seems that Ishpakai of the Scythians died in battle against the Assyrians. Bartatua became a leader of the Scythians in his stead. It is possible that Bartatua married an Assyrian princess around this time, but this is unclear. The accession of Bartatua to the Scythian leadership saw the beginning of a strange alliance that lasted until the later stages of the empire.

|

| Inscription of Esarhaddon |

Inscription of Esarhaddon, 2, written around 675

Also in 675 Esarhaddon made a treaty with Baal I of Tyre detailing Baal’s obligations as a vassal of Assyria. It was likely that the Assyrians suspected the rulers of the region of consorting with the Egyptian Pharaoh Taharqa and were trying to bring them firmly under control. Around this time Esarhaddon also forces the kings of the region to give large tributes of building materials to aid his construction projects. The kings of the Levant had perpetually sought Egyptian aid in their revolts against Assyria and Esarhaddon’s next campaign would be against Egypt.

In 674 Sharru-Nuri was Limmu of Assyria. The Assyrian army, or part of it, marched to Samele, a fortified town near Babylonia. Possibly this was to put down the troublemaking of Sillaya, but we do not know the details. I do not think we hear any more of Sillaya’s rebellion however. The Elamites returned some gods that had been taken in previous attacks on Babylonia, presumably as part of Esarhaddon’s policy of appeasing the Babylonians, and there appears to have been a peace treaty between Elam and Assyria around this time.

The seventh year: On the eighth day of the month Addaru the army of Assyria marched to Shamele. In that same year Ishtar of Agade (Babylon) and the gods of Agade left Elam and entered Agade on the tenth day of the month Addaru.

Babylonian Chronicles, (Esarhaddon Chronicle), written around 660?

In 673 Atar-ili was Limmu of Assyria. In March 673, (near the end of the Assyrian year) the Assyrians launched their preliminary attack on Egypt and were defeated by the Kushites under Taharqa. The Babylonians record the defeat, but the Assyrians do not. If Egypt was to be taken it would have to be with a substantial army. This attack was almost certainly only done with a small portion of the army, as there were developments happening elsewhere.

Baal I of Tyre took advantage of the Assyrian defeat to launch a rebellion against the Assyrians in conjunction with the triumphant Pharaoh Taharqa of Egypt. Esarhaddon was unable to respond as his army was engaged in a rather unique campaign against the kingdom of Shubria.

|

| Inscription of Esarhaddon |

Shubria seems to have had an unusual religious custom attached to its kingdom however. They seem to have allowed refugees from all kingdoms to flee to their kingdom where they would be given sanctuary and they would defy even the Assyrian emperors to protect those who had sought refuge with them. This policy was met with bafflement by the Assyrians, but in 673 some refugees fled to Shubria who could not be tolerated to remain. It is not stated, but it is possible that the refugees were the brothers of Esarhaddon, Ardi-Mullissu and Shareser. These were the murderers of Sennacherib and threats to the Assyrian dynasty and could not be tolerated in any allied state. Whoever the refugees were Esarhaddon demanded that they be taken from the sanctuary and handed over to the Assyrians to face justice. Rusa II of Urartu had made similar demands of Shubria and had been refused, so the Urartians would not help against the Assyrians. Even though Esarhaddon seems to have made some guarantees for safety of the criminals, the tiny kingdom of Shubria, driven by religious obligations, refused his demand. This refusal triggered a full-scale Assyrian invasion.

…Robbers, thieves, or those who had sinned, those who had shed blood, ... officials, governors, overseers, leaders, and soldiers who fled to the land Shubria … thus I wrote to him, saying: “Have a herald summon these people in your land and … gather them and do not release a single man; ... have them brought before the goddess Piriggal, the great lady, in the temple;... a message concerning the preservation of their lives ... let them take the road to Assyria with my messenger.”

Inscription of Esarhaddon, 33, written around 673

The Assyrian army invaded the land without much opposition, as Shubria was a minor state and could not have resisted the army in the field. The king of Shubria seems to have tried to bargain against the irresistible might of the invaders, offering to make his kingdom into an Assyrian province and to give full restitution for the refugees. As the Assyrian war machine was in motion, this offer was refused. The city of Uppume was attacked and we are given a rather intriguing picture of the siege. The Assyrians attacked the wall surrounding the city and by around September, were on the verge of breaching the wall, using a siege ramp of earth, wood and stone.

During the night the Shubrians rallied forth and poured a mixture of oil and burning tar on the siege ramp to try and burn the wooden sections supporting it. The main Assyrian army seems to have been campaigning elsewhere in the region, having left a force to man the siege, and if the Shubrians could burn the ramp it might buy them time. However, fate was against them and the wind turned back on the city, where the fire caught and began to consume it. The Assyrian siege troops seized the initiative and captured the city with great bloodshed, however the citadel still held out against the Assyrians.

|

| Assyrian soldiers besieging a city |

Inscription of Esarhaddon, 33, written around 673

Ik-Teshub, the king of Shubria, then attempted a propitiatory ritual. A life-size statue coated in gold (presumably all the gold that remained in the citadel) was made to represent the Shubrian king. It was placed in chains for slavery, wearing sackcloth for sorrow and holding a millstone to represent menial labour. The sons of the king took this offering to Esarhaddon, begging him to show mercy to their father and transfer the sins of the father onto the statue in his likeness. The ritual failed. Esarhaddon would not show mercy and, in his inscriptions, makes a speech saying that it is too late.

You bathe after your offerings! … You put in drain pipes after the rain! … The highest divine orders have been spoken twice. Your days have elapsed! Your appointed time is here! … The carrying off of your people was decreed. … This destiny is firmly fixed and its place cannot be changed.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, 33, written around 673

After this strange, sad campaign against a tiny buffer state Esarhaddon captured those who had taken refuge there. The captives were mutilated and executed, but it is not clear if Ardi-Mullissu or Sharezer were captured here. Ik-Teshub, the king who had offered shelter to the refugees of the surrounding empires, was executed. The kingdom of Shubria was divided into two provinces and directly ruled by the Assyrians. As a peace offering to the Urartians, Esarhaddon took the refugees who had fled from Rusa II and handed them over. This act of diplomacy seems to have kept the Urartian kingdom happy with Assyrians for the time being. After the wars decades earlier Urartu was in no hurry to clash again with Assyria.

Esarhaddon had had his army campaigning in Iran around this time. He had made an alliance with Bartatua of the Scythians and slain Ishpakaia. Kashtariti of the Medes was forced to stop his attacks around this time and Esarhaddon received tribute and submission from the horse tribes of the Medes. The horse tribes of Umman-manda, Scythians, Cimmerians and Medes seem to have formed loose coalitions that operated at the edges of the Assyrian empire that merged and collapsed with bewildering frequency. But during the reign of Esarhaddon they seemingly gave no further problems. The chronology is confused and this series of campaigns may have happened around 675, but it is enough to know that the Medes and Scythians were now mainly pacified.

|

| Inscription of Rusa II |

Inscription of Esarhaddon, 2, written around 675

In 672 Nabu-beli-usur, governor of the city of Dur-Sharrukin, was the Assyrian Limmu for the year. In this year Sin-iddina-ala, the Crown Prince of Assyria and heir to Esarhaddon, died. Esarhaddon had come to power in a confused kin-strife after the death of the main heir and the subsequent assassination of his father. To prevent any similar strife on his passing, Esarhaddon designated one of his younger sons, Ashurbanipal, as Crown Prince of Assyria and also confirmed that his older brother, Shamash-shuma-ukin, would be King of Babylon when Esarhaddon died. The Assyrians had to swear oaths of fealty and the subject nations and allies of the empire were also obliged to swear allegiance to the future princes. Some Assyrians were concerned about making kings of both of his sons. Even with Babylon subordinate to Assyria, some were concerned that the division of power would be dangerous for the empire. But it fit with Esarhaddon’s policy of the restoration of Babylon and might have been intended to conciliate the older son, Shamash-shuma-ukin, and stop him from attempting to seize the throne. A copy of the succession treaty with a vassal king of the Medes has been preserved.

When Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, passes away, you will seat Ashurbanipal, the great crown prince designate, upon the royal throne, and he will exercise the kingship and lordship of Assyria over you. You shall protect him in country and in town, fall and die for him. You shall speak with him in the truth of your heart, give him sound advice loyally, and smooth his way in every respect.

Succession Treaty of Ashurbanipal imposed by Esarhaddon on the Median ruler Humbaresh: written around 672

Not only had Sin-iddina-ala, the crown prince died, but Esarhaddon also lost his main wife Ashur-Hamat in the year 672. Esarhaddon frequently consulted oracles, astrologers, doctors and all who could promise to tell the future or in some manner cheat death. He appears to have suffered from an unspecified wasting illness, which was present before his accession to the throne, but which intensified as he grew older. There would be periods when the king was quite well, but would then relapse and seek aid from the doctors, priests and gods. The illness was a rare one, as his doctors were unable to even recognise it, let alone cure it. Simo Parpola has made the tentative diagnosis that lupus may have been the disease. Esarhaddon is sometimes referred to as superstitious and paranoid, but the knowledge that he was suffering from an incurable disease that gave him frequent pain, disfigured his appearance and left him prone to depression might explain some of his behaviour. From 672 onwards his son Ashurbanipal, and Ashurbanipal's mother Zakutu, would take up much of the responsibilities of governing the empire when Esarhaddon was incapacitated with illness.

The treaty of Zakutu, the queen of Sennacherib, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, with Shamash-shumu-ukin, his equal brother, with Shamash-metu-uballiṭ and the rest of his brothers, with the royal seed, with the magnates and the governors, the bearded and the eunuchs, the royal entourage, with the exempts and all who enter the Palace, with Assyrians high and low: Anyone who is included in this treaty which Queen Zakutu has concluded with the whole nation concerning her favourite grandson Ashurbanipal…

Succession Treaty of Ashurbanipal, promulgated by Queen Mother Zakutu

In 671, while Tebeta was the Assyrian Limmu for the year, Esarhaddon’s fit of illness had passed and Esarhaddon and the Assyrian army moved against Egypt. The preliminary attack of 673 had failed through insufficient forces and planning, so a much larger army went with the king, who was personally overseeing the attack, in what he referred to as his tenth campaign, implying at least one campaign per year. The Assyrian army moved to Haran in northern Mesopotamia where Esarhaddon received a prophecy from the temple of the moon God Sin at Haran. It is possible that Esarhaddon patronised this god because he had been exiled in the region under the reign of his father, or alternatively because he believed that Sin could heal him of his disease. The prophecy was favourable and Esarhaddon marched to the Levant, crossing the Euphrates during the spring floods in his urgency to have as much campaigning time against the Egyptians as possible.

|

| Column of Taharqa in Karnak |

Letter to Ashurbanipal, written around 668BC

While travelling through the Levant it seems that the Assyrians paused to attack Tyre, before Baal I of Tyre submitted and paid a substantial tribute. Taharqa of Egypt was unable to come to his aid in time, so submission was the wise policy, even for a fortress as impregnable as Tyre. Esarhaddon took away his provinces and assigned them to Assyrian governors and moved on swiftly to the Brook of Egypt, marching from Aphek to Raphia. From here he had a system of water supplies laid out to help his troops across the desert. He had dug a number of wells and sent ahead Arab allies with water-laden camels to create supply dumps for the army. The entire march across the desert seems to have taken under a month before the army reached a fortress city that the Assyrians name Ishupri, but which is probably a corruption of an Egyptian word meaning “Fortress of Seti”.

By means of ropes, chains, and sweeps, I provided water for my troops drawn from wells. In accordance with the command of the god Asshur, my lord, it occurred to me and my heart prompted me and thus I collected camels from all of the Arab kings and loaded them with water skins and water containers.

Inscription of Esarhaddon, written around 670 (Inscription 34)

Around the city of Ishupri, Taharqa had drawn up his army and while the initial clash favoured the Assyrians, the Kushites and Egyptians fought well. The Assyrian march towards the city of Memphis was slow, with fifteen days of near continuous battle (or at least three major battles on the 3rd, 16th and 18th days of the month Du’uzu). Esarhaddon claims to have wounded Taharqa five times, but this can be written off as hyperbole. In fact Esarhaddon seems to have gone into hiding in his camp, fearing portents of doom and invoked the substitute king ritual.

|

| Inscription of Esarhaddon on left |

Inscription of Esarhaddon written around 670 (Inscription 98)

The substitute king ritual was one that Esarhaddon had done before. If there was a prophecy the king would die (usually tied to a lunar eclipse), the king would go into hiding for 100 days and be referred to by a codename, which in Esarhaddon’s case was “the farmer”. Meanwhile a criminal or a commoner would be placed upon the throne and referred to as king for the 100 days, after which the substitute was murdered, the prophecy fulfilled and “the farmer” would emerge from hiding and reclaim the throne, safe from the heavenly portents. This ritual was one that Esarhaddon did a lot and it was unpopular with his subjects, but may have been used to protect the king’s life from conspiracy.

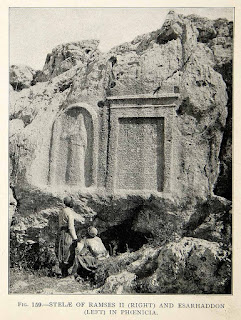

Memphis was attacked from the land and from the river by Esarhaddon, with ships being outfitted with towers and floated down the Nile to attack the walls. The Egyptians and Nubians fought fiercely, but the city fell to the Assyrians very swiftly, and Taharqa had to flee from the city. While Taharqa managed to escape, his family were not so lucky. His Crown Prince was captured, Ushanahuru, and other members of his family, including at least one of his wives, seem to have been taken prisoner in the fall of Memphis. Memphis was plundered and vast treasure sent back to Nineveh, stamped with the name of Esarhaddon. The Assyrians appointed governors, some Egyptian and some Assyrian, of the various provinces of northern Egypt and Esarhaddon marched back through the Levant, placing monumental victory stelas on his way. Despite the fact that Taharqa had escaped, news may have arrived that forced Esarhaddon to return swiftly to Assyria.

|

| Victory Stela of Esarhaddon |

Inscription of Esarhaddon written around 670 (Inscription 98)

Taharqa was an energetic and powerful Pharaoh who had fought the Assyrians before, but who had never suffered such a defeat. Egypt had not successfully been invaded from across the Sinai since the time of the Hyskos before the New Kingdom. As Pharaoh, he would have been the divine representative of the gods, so this disaster must have shaken his personal beliefs to the core. A letter or prayer from Taharqa to the god Amun contains a heartrending plea for the god of the Egyptians to protect Taharqa’s family in captivity and bring him victory once more. Taharqa seems to have believed it was his divine destiny to take back the throne of Egypt and even as he fled to Kush, he was planning his return.

Oh Amun, … my wives, let my children live. Keep death away from them, for me.

Prayer of Taharqa, written around 670

Esarhaddon had meanwhile heard of a planned revolt against the monarchy. While Esarhaddon was in Egypt, a prophetess in Harran had proclaimed a man called Sasi to be the new king of Assyria. He appears to have been a member of the Assyrian royal family, but probably a distant relative of Esarhaddon’s rather than a brother. He had powerful supporters, including the chief eunuch of the palace in Nineveh and the rebellion was a serious one.

A slave-girl of Bel-ahu-uṣur [...] upon [...] in a suburb of Harran; since Sivan (III) she is enraptured and speaks nice words about him: 'It is the word of Nusku: The kingship is for Sasi. I will destroy the name and seed of Sennacherib!'"

Letter sent to Esarhaddon detailing a plan to kidnap the prophetess from the house of Sasi (SAA 16:059)

So it seems that the prophecies of Sasi’s kingship took place around May or June, while Esarhaddon was still campaigning in Egypt. The rebellion must have grown in strength over the next few months and it is possible that there were rumours that Esarhaddon was dead. The Assyrians defeated the Kushites around July and marched back towards the Levant some months later. The conspirators of Sasi were operating quite openly and some officials followed the king while others backed the divinely ordained usurper. Letters flew back and forth with officials accusing each other of treason and informing on their superiors. Around November/December (Tebetum), Esarhaddon declared another substitute king ritual and went into hiding. This time the king’s life really was in danger. When the hundred days of the ritual were complete Esarhaddon re-emerged with his plans in place and a bloody pogrom ensued, with Sasi’s supporters being hunted down.

|

| Taharqa's son and Baal I as prisoners |

Babylonian Chronicle: Nabonassar to Shamash-shuma-ukin describing the year 670

670 opened with the massacre of officials in Assyria and other parts of the empire, including Harran and Babylonia. Shulmu-beli-lasme was the Limmu for the year and while the revolt of Sasi was crushed in Assyria, a new revolt was launched in Egypt. The Egyptians were far from happy at the reign of the Assyrians, and the Kushites to the south aided and abetted the revolt; with Taharqa wishing to retake the throne. The new officials put in place by Esarhaddon were either killed or joined the rebels. In fact the officials may have been some of the prime instigators of the rebellion. Esarhaddon was in no condition to deal with this new threat. After the harsh campaign and the strain of rebellion his sickness flared up again and Esarhaddon was very ill indeed. At this point, his son Ashurbanipal and Esarhaddon’s mother Zakutu were taking over some of the administration of the empire while the king hovered on the brink of death.

On a rather lighter note, the Assyrian royal family at the time seems to have taken great pride in its literacy and the Crown Prince Ashurbanipal was an avid reader and writer. His sister, Sherua-etirat, was also quite proud of her literary abilities. We have a letter from around this time, from Princess Sherua-etirat to Libbali-sharrat, the wife of Ashurbanipal, scolding her for not studying hard enough and working on her homework. It is a strange personal touch in the midst of the tales of rebellion, sickness and conquest of the times, and a reminder that have been shirkers of homework and nagging family members for millennia.

Word of the king's daughter to Libbali-sharrat. Why don't you write your tablet and do your homework? For if you don't, they will say: "Is this the sister of Sheru'a-eṭirat, the eldest daughter of the Succession Palace of Asshur-etel-ilani-mukinni, the great king, mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria?" Yet you are only a daughter-in-law — the lady of the house of Ashurbanipal, the great crown prince designate of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria!

Letter from Sherua-etirat to Libbali-sharrat, written around 670 (SAA 16 028)

In 669 Shamash-kashid-abi was Limmu of Assyrian. Esarhaddon’s health recovered slightly and he began the march from Nineveh to Egypt later in the year. But as he was in Harran, around the month of October/November there was a final bout of illness and Esarhaddon died. His sons, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shuma-ukin became kings of Assyria and Babylon respectively, with Ashurbanipal being the senior ruler. There was no real resistance to their takeover. The subject nations and surrounding empires were too weak for any resistance and the crushing of the rebellion in 670 had squashed any internal threat to the succession.

|

| Zakutu and Esarhaddon |

For Esarhaddon’s legacy, he is a hard king to read. He was weak and sickly, but under his rule the armies of Assyria humbled Elam and Egypt. In some ways Esarhaddon expanded the empire and left the empire stronger than it had ever been before. His conquest of Egypt was incomplete, but no Assyrian king had ever done so much. He was a destroyer of cities, but also restored Babylon. He was merciless at times, particularly when dealing with rebellions towards the end of his life. But he is almost unique among the Assyrian kings recorded as occasionally showing mercy as well. He was sickly, but capable of fast action when the time required it. He was possibly the most superstitious king in a superstitious age, but he was also quite cunning and able to use prophecies and astrology to his advantage. In short, despite having so many sources available to us, Esarhaddon was, is, and probably forever shall be, an enigma.

In 668 Marlarim, Field Marshall of Kummuhu, was the Limmu of Assyria. Shamash-shuma-ukin was crowned king in Babylon at the Akitu Festival for the Babylonian New Year. The rebuilding of Babylon was nearly completed by the time Esarhaddon died and the first years of Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shuma-ukin saw the gods return from Assyria with great pageantry and pomp, sailing on barges down the river before marching in ceremonial processions to their gilded temples. In all the descriptions of war it can be easy to forget that people’s lives were still filled with ceremony and celebration, even if some of the buildings were primarily paid for with war-loot. There seem to have been some expeditions against tribesmen near the city of Der, near the Elamite frontier and it seems that the agriculture and economy of the Assyrian empire were flourishing at this time.

|

| Ashurbanipal Lion Hunt Relief |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 650 (Inscription 4)

In 667 Gabbaru, the governor of Dur-Sennacherib, was Limmu of Assyria; the Eponym for whom the year was named in certain Assyrian records. Ashurbanipal had established his rule in Assyria, seen his brother enthroned as a subordinate ruler in Babylon, carried out the required religious rituals, begun various building activities and sent his army to punish some mountain tribes. Now, the new king Ashurbanipal turned his attention to Egypt, where Taharqa was trying to retake the Nile Delta. The army would have marched to Harran, where Ashurbanipal was to install a younger brother as priest of the moon god Sin, before passing south across the Euphrates and through the Levant. Mitinti II of Ashkelon paid tribute to the Assyrians along with 21 other kings, including Manasseh king of Judah and the unreliable Baal I who had been in revolt previously against the Assyrians.

Taharqa had retained Thebes and had retaken Memphis, expelling the Assyrian city governors and minor Egyptian princes who had allied with the Assyrians during Esarhaddon’s conquest. Ashurbanipal, moved down the coast of Palestine and marched his army across coast of the Sinai desert, with the Phoenician fleets moving along the coast along with his army. He engaged Taharqa in battle near Memphis and the Kushites and Egyptians were defeated. Taharqa fled to Thebes, while Ashurbanipal seems to have returned to Assyria with most of his army, leaving an expeditionary force in Egypt to ward off the Kushite threat.

|

| Taharqa offering wine to the god Hemen |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

When Taharqa was defeated the princes and rulers of the Nile Delta seem to have feared the expeditionary force left by the Assyrians and attempted to switch sides, sending messengers to Taharqa and asking him to return and drive out the Assyrians. Unfortunately for these rulers their messages were intercepted by the Assyrian generals, who imprisoned the rulers and sent them to Nineveh to face royal judgement. The cities of Sais and other cities in northern Egypt were devastated by the Assyrian generals, who punished the attempted rebellion harshly. Of the twenty local rulers sent as prisoners to Nineveh, one of them, Necho I, appears to have had a golden tongue, as he persuaded Ashurbanipal to pardon his rebellion and to have him sent back to Egypt as a deputy ruler for the whole country of Egypt. Perhaps Ashurbanipal realised that Egypt was too distant and too culturally different to be ruled as a mere province and would work better as an allied kingdom.

As for those twenty kings who had constantly sought out evil deeds against the troops of Assyria, they brought them alive to Nineveh, before me. Among them, I had mercy on Necho and I let him live. I made his treaty more stringent than the previous one

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

In 666 Kanunayu, governor of the new palace, was the Assyrian limmu for the year. The campaign in Egypt ended with Necho I enthroned as an Assyrian vassal Pharaoh. In Assyria the astrologers read the stars as best they could and determined that there was a prophecy of the death of the king. Ashurbanipal went into hiding for about twenty days while a substitute king ruled and was then killed to fulfil the prophecy.

| |

| Kushite Royal Cemetery at Nuri |

Also in this year, relations between Elam and Assyria, which had been relatively friendly during the reign of Esarhaddon, broke down. Ashurbanipal had previously sent food supplies to Elam during a famine, so this act of war would have been seen as a great betrayal. The Elamites were allied with the Gambulu tribe and raided into Babylon, but do not seem to have accomplished much in their attacks.

In 664 Sharru-lu-dari, governor of Dur-Sharrukin, became the Assyrian limmu official for the year. Tantamani tried to begin his reign by attacking Necho I in Memphis and seems to have killed the vassal Pharaoh there. Necho’s son, Psammetichus who had been the ruler of the city of Athribis, fled to Assyria to seek aid against the Kushites. The Assyrian army marched from Nineveh back to Egypt once more. Tantamani abandoned Memphis and fled to Thebes, where the Assyrian army now followed. Fearing that Thebes itself would fall, Tantamani withdrew southwards towards Kipkipi while the Assyrians began the siege of the city. Thebes was the sacred city of the god Amun and had been fortified by different Pharaohs for over a millennia. Nevertheless it was taken and vast plunder taken back to Assyria. This conquest probably marks the highest point of Assyrian power and would be remembered by the enemies of Assyria.

|

| Tomb of Tantamani |

Nahum 3:8-10, written around 630-600BC

Earlier in the year, Urtaku, king of Elam, had unsuccessfully attacked Babylonia and been driven off. Teumman took the throne of Elam in his stead. Teumman may have been a brother of Urtaku, but may have also been an outsider. Either way, he was a usurper and attempted to have the children of Urtaku murdered. Rather than wait for the purge, the Elamite royal family fled to the court of Ashurbanipal. Teumman, trusting in the strength of the Elamite kingdom, sent insulting messages to Ashurbanipal demanding the return of the refugees, while the Elamite princes begged Ashurbanipal to punish the usurper. I am unsure of the chronology here. Many sources seem to place this event in 664, but I think that 654 might make more sense when examining some of the inscriptions.

From 663 to 653 the chronology becomes somewhat confused. It is unfortunate that the Assyrians had a perfectly reasonable method of dating with the limmu system, but on many royal inscriptions, simply do not use it. Thus the dates are a little speculative. We know what happened, or at least, what the Assyrians say happened, but we cannot exactly say when it happened or what order it happened in.

The Assyrian field army moved against Tyre, probably around 663, setting up blockades against the city, but being unable to seriously threaten the island stronghold. Tyre was built on the coast, with some houses and temples near the shore, while the palace, main temple and the majority of the important buildings were on an island close to the shore. The island was heavily fortified and the people of Tyre had a large navy at their disposal. Large storehouses provided the city with food during a siege, even if their fleets were unable to supply them. Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians would have found it very difficult to take the city by direct assault. However, unlike later sieges of Tyre, the inhabitants had no hope of rescue and with the ships of Cyprus, Byblos and Sidon at their disposal, the Assyrians could deny the sea to the trading rulers of Tyre. Baal I of Tyre decided to strike a deal and sent his son to submit to Ashurbanipal, offering to pay a heavy indemnity and offering hostages from the royal family in exchange for lifting the siege.

|

| Ashurbanipal Lion Hunt Relief |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

Ashurbanipal now received the tributes and submissions of the various kings. The king of Arwad (probably in Cyprus) sent a daughter to serve as a housekeeper, as did the kings of Tabal and Cilicia. Most unusually Ashurbanipal received a message from Gyges, king of Lydia, on the western shore of Asia Minor. According to Assyrian records Gyges had been facing troubles with the invading Cimmerians. He then had a dream counselling him to submit to Ashurbanipal and only then he would defeat the barbarians at the gates. Ashurbanipal recounts that messages arrived and that shortly thereafter, Gyges won a resounding victory against the Cimmerian horse nomads and that their captured chieftains were sent to him in chains, conquered by the mere invocation of his name. This is an unusual tale and there may be more to it than meets the eye. But it is interesting to see Gyges being mentioned by both Archilochus and Ashurbanipal. There may have been campaigns against the kingdoms of Anatolia that prompted these surrenders, rather than happening purely voluntarily as Ashurbanipal suggests.

|

| Cuneiform tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

There was an Assyrian campaign against Ahseri, the king of Mannea (a kingdom in present-day northwest Iran). Ahseri fled from the Assyrian army, but was slain in a coup and his son Ualli took the throne and submitted to Ashurbanipal, whose armies were seemingly invincible at this point. Hostages were sent to the Assyrian court of Nineveh, which by now resembled an international melting pot of royal hostages and Ualli agreed to pay a tribute of horses. A campaign was also undertaken against the Medes in the vicinity, with Ashurbanipal boasting of capturing seventy-five cities and capturing the enemy rulers alive.

Ishtar placed Ahseri in the hands of his servants and then the people of his land incited a rebellion against him. They cast his corpse into a street of his city and dragged his body to and fro. … Afterwards, Ualli, his son, sat on his throne.

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

A governor of Urartu had attacked an Assyrian city but was killed in the attempt and his head was taken to Nineveh. However Rusa II and Ashurbanipal did not go to war over the incident. This attack may have been part of the Mannean campaign or might have been part of a separate war. The Urartian inscriptions are not detailed enough to describe their kingdom in detail at this time; also they are far harder to access than the Assyrian inscriptions. Despite the slight lack of sources Rusa II seems to have been a powerful king who was treated with respect by the Assyrians.

For Khaldi, the mighty, the lord, this shield Rusa, the son of Erimenas has dedicated, and the shield bearers, for the gods, the children of Khaldi, the multitudinous. Belonging to Rusa son of Erimenas.

Inscription on a shield dedicated by Rusa II to the Urartian chief god Khaldi, written anywhere between 680-639

In Assyria and Babylon Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shuma-ukin embarked on an ambitious building program that saw walls, canals and temples repaired. The two brothers were both literate and intelligent and had a great sense of the past. So, as they repaired the temples they would leave their inscriptions beneath the foundations, but also carefully restore the inscriptions of previous kings, so that the achievements of their forebears would be remembered as well. This was a standard practice in Mesopotamia and the brothers seem to have mentioned each other in their inscriptions.

For the god Shamash, king of Sippar, his lord: Shamash-shuma-ukin, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, reconstructed Ebabbar ( the “Shining House”) anew with baked bricks for the sake of his life and for the sake of the life of Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria, his favourite brother.

Inscription of Shamash-shuma-ukin on the reconstruction of the main temple of Shamash in Sippar. (Inscription 2), written around the 660’s.

What was unusual was the Library of Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal was literate and claimed to have been trained in all the areas of knowledge prized by the Mesopotamians, including being adept at reading and writing in not only Assyrian/Akkadian, but also in Sumerian. He made an attempt to gather copies of all the writings of the civilisation in a great library in Nineveh. It is unclear how far he succeeded, but a great percentage of our knowledge of his civilisation comes from this library. It was a far-sighted thing to attempt and in certain ways pre-empted the later, much larger, Library of Alexandria.

|

| Cuneiform tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 650 (Inscription 11)

In Egypt, Psammetichus, the son of Necho I and vassal ruler for the Assyrians, was not idle. Tantamani had been expelled from Thebes and Thebes was looted (although the Assyrians seem to have not deliberately destroyed the temples at Karnak). However, the Kushites still seem to have had a major presence in the city. This was at least partly because the Divine Adoratrice of Amun (High Priestess) was a sacred figure and had been left alone by the Assyrians and Egyptians. This person had joint control over the city of Thebes and control of the vast estates of the temple of Amun. The current Adoratrice was Shepenupet II, a Kushite and a long-lived daughter of Piye, the first Kushite Pharaoh of Egypt. Shepenupet was old and had adopted a daughter, Amenirdis, the daughter of Taharqa, to succeed her.

The estates of Amun were too powerful to be left in the hands of the relatives of a rival Pharaoh, so Psammetichus (or Psamtik I depending on what naming convention is used), decided to force Shepenupet to adopt his daughter, Nitocris, instead, so that on Shepenupet’s death, Nitocris would become the next Adoratrice. This forced adoption took place in 656 and is commemorated by a stela of Psammetichus. This time period sees Psammetichus gradually increasing his power to the point where he would be able to defy the Assyrians and expel them from his land. Assyrian forces may have begun to withdraw from Egypt from around 654 onwards.

|

| Nitocris and Psammetichus I worshipping |

Adoption Stela of Nitocris

Psammetichus was also famed in literature for conducting possibly the first scientific experiment ever, or at least the first psychological experiment. The Egyptians had always claimed that they were the oldest civilisation in the world. Psammetichus sought to prove this by having some children raised without listening to the speech of others and trying to figure out which language the children would spontaneously speak, assuming that they would speak the original language of mankind and thus, find the oldest civilisation. This experiment supposedly showed that the Phrygians were the oldest civilisation, which is interesting, as that can hardly have been the expected outcome. This was determined by the fact that the children kept saying the word “bekos” when pointing at bread, which roughly matched the Phrygian word for bread, but not the Egyptian. However, this story is nowhere recorded among the Egyptians and is only taken from the much later Greek texts of Herodotus.

|

| Sarcophagus of the steward of Nitocris |

Herodotus, Histories, 2.2.3-4

While we cannot prove if the language experiment was real or not, we can be certain that a new form of writing was pioneered in Egypt around this time, called the Demotic script (capitalised to avoid confusion with Greek “demotic” script). This was a short-hand script that could be used to transcribe hieroglyphs quickly and in some ways replaced an earlier short-hand known as hieratic. It was not an alphabet but it could be used to speed up writing and was widely adopted. It was part of the much later Rosetta Stone that was later used to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

|

| Elamite relief showing a woman spinning |

Concerning the aforementioned fugitives, Teumman sent insults monthly by the hands of Umbadara and Nabu-damiq. Inside the land Elam, he was bragging in the assembly of his troops. … I did not send him those fugitives.

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

On July 13, 653BC, a lunar eclipse occurred over the Middle East. This was recorded rather strangely by the Assyrians (where it is described as lasting for an unusually long time) and interpreted to mean that Elam will fall by the will of the gods. This may have been a rather creative interpretation and the Elamites also mustered their troops, confident in victory. Teumman was then supposedly stricken with a seizure and partial paralysis but nevertheless continued as an active foe. This seems like propaganda, but a contemporary letter seems to suggest that this actually happened. If the account of the seizure is not hyperbole then the disfigured usurper must have been a terrible sight to behold.

|

| Ashurbanipal Lion Hunt Relief |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

Having heard that the king of Elam had suffered a stroke and that several towns had revolted against him saying: "We will not remain your subjects", I wrote to the king, my lord, what I had heard.

Letter from the Chaldean official Nabu-bel-shumate to Ashurbanipal, written around 653

The Elamites had fallen back to the Ulai River, now known as the Karkheh River and flowing with a different modern course, which flowed to the north and west of one of their capitals, Susa. There they made their stand at what is known as the Battle of the Ulai River, trying to deny the Assyrians the water sources. A bloody battle followed and the Elamites were defeated on the banks of the river and in a small fortress nearby known as Til-Tuba. There may have been a civil war in Elam at the time. Later sources speak of a king of Elam called Atta-hamitti-Inshushinak who may have been ruling at this time. When Teumman lost the battle he did not retreat to Susa, nor did Ashurbanipal besiege it. Instead Teumman and at least one of his sons fled to a nearby forest.

I brought about their defeat inside Til-Tuba. I blocked up the Ulai River with their corpses and filled the plain of the city Susa with their bodies…

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

|

| Cuneiform tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal |

I placed Ḫumban-nikas II, who had fled to Assyria and had grasped my feet, on his Teumman’s throne.

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

Not content with such a great victory, Ashurbanipal followed up his victory with a campaign against the Aramean tribe of Gambulu, led by the unfortunate Dunanu and supported by some additional troops of Teumman. These were defeated at the siege of Sha-pi-bel and Dunanu was captured alive. A series of torments were carried out on Dunanu, with the severed head of the allied Elamite commander being used to beat him. He then was marched back to Nineveh in chains with the severed head of Teumman carried around his neck, and was forced to watch the torture and execution of his advisors and commanders before being killed himself. The Assyrians were cultured at times, but utterly horrifying in their treatment of defeated foes. When the envoys of Teumman saw the fate of their ruler they are said to have killed themselves in fear and terror. The vengeance continued in an orgy of killing, when the grandson of Merodach-Baladan was extradited by the new king of Elam to appease Ashurbanipal. The tribe of Gambulu was blamed for conspiring with Teumman and for leading Urtaku astray, so even the bones of their tribal leaders were carried to the gates of Nineveh where his captive descendants were forced to grind up and destroy the bones of their ancestors.

|

| A banqueting scene showing Ashurbanipal and his queen Libbali-Sharrat dining, with Teumman's head hanging from a tree to the left |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

It is unclear why there was such vengeance taken. I could be wrong but this seems extreme even by the standards of Assyria. It was also dangerous, as Assyrian armies were arguably already over-extended in Egypt, which they were in danger of letting slip from their grasp. Perhaps history will tell us more about this feud between Teumman and Ashurbanipal that will reveal why this war turned from a standard conflict between powers to something more resembling a genocide. Assyria does seem to have been under serious threat at this time. A king of the Medes, Phraortes seems to have died in battle against the Assyrians around this time. Possibly this was part of a coordinated invasion of the empire, with Teumman as the possible mastermind of the alliance, or perhaps a high-ranking malcontent within the empire itself.

Around this time it appears that Gyges of Lydia, who had previously submitted to Assyrian rule as a way of defeating the Cimmerians, broke away from the Assyrian empire and sent troops across the Mediterranean to Egypt. These troops assisted Psammetichus in expelling the Assyrian officials and from this point on Egypt is once again independent and under the control of Psammetichus, whose dynasty is known as the Saite Dynasty or the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Even though this rebellion was noted by Assyria, Ashurbanipal does not seem to have made any attempt to retake Egypt. Perhaps the Assyrians realised that Egypt was too powerful and too distant to fully control and Psammetichus seems to have stayed on relatively friendly terms with the Assyrian Empire. It is hard to know exactly what happened here, but after this time Egypt effectively had full independence from Assyria. Ashurbanipal cursed Gyges and prayed for his demise, but his troops were fully committed in the east of the empire.

He sent his forces to aid Psammetichus, the king of Egypt who had cast off the yoke of my lordly majesty, and then I myself heard about this and made an appeal to the god Asshur and the goddess Ishtar, saying: “Let his corpse be cast down before his enemy and let them bring me his bones.”

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

In 652 Ashur-dan-usur, governor of Barhalzi, was the Assyrian limmu official for the year. This year Shamash-shuma-ukin, king of Babylon, launched a rebellion against his brother Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria. Babylon was a proud and ancient city, with a tradition of empire in the region, stemming back to the time of Sargon of Akkad, sixteen hundred years previously. Shamash-shuma-ukin was the elder of the two brothers and resented the fact that Babylon had to serve Assyria and that he had to serve his younger brother. It is quite possible that he had in fact been planning the rebellion with Teumman and Phraortes the previous year and that Teumman had revealed his hand too soon. This might explain why Ashurbanipal had such hatred for Teumman; that he suspected a betrayal of the deepest nature. Perhaps the brutality against the Elamites and Gambulu tribesmen was meant to deter an impending revolt. We cannot tell for sure. Babylonians had been raising troops throughout the land for over six months and on the 19th day of the month Tebetu in the year 652, full hostilities broke out between the two lands and the two brothers.

|

| Assyrian soldiers |

Babylonian Akitu Chronicle, written around 620’s

The two armies did battle at a place called Hiritu about two months after the war began, and the Babylonians were defeated heavily. The Assyrians pressed on into Babylonia and the troops of Shamash-shuma-ukin withdrew to the fortified cities of Borsippa, Babylon and others. Tribes of Arabs were called in as allies by Babylon and the Elamites were also called. Despite the fact that he had been appointed by Ashurbanipal, Humban-Nikash II of Elam joined the war on the side of Babylon and sent troops, including some of the sons of Teumman, to fight Assyria, exhorting them to seek revenge.

The Elamite troops marched towards Babylonia and were intercepted by the Assyrians, who defeated them and cut off the head of Undasu, the son of Teumman, at the battle of Hirit/Mangisi. Ashurbanipal sent urgent messengers to Humban-Nikash II to determine if this was an official assault, or if these were rebellious troops led by the faction of the previous king. Humban-Nikash made no reply, but did imprison the messengers. However, before any further scheming or warfare could ensue, Humban-Nikash II was murdered by another member of the royal family, known to history as Tammaritu II (probably not the Urtak's son Tammaritu who had previously submitted to the Assyrians, but a different hitherto unknown Tammaritu). Elamite politics now resembled a rather bloodier version of Game of Thrones. Instead of making peace with Assyria, Tammaritu II decided to continue the war.

In 651 Sagubbu, the governor of Harran, was Assyrian limmu for the year. Tammaritu II had tried to continue the war against Assyria, but had only been reigning for a few months before one of his generals, Indabibi, launched a coup against him and Tammaritu II had to flee for his life to his enemy Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal spared his life and the life of his family and the war continued, with Indabibi, the newest usurper of the Elamite throne. It is unclear if Indabibi continued the war against the Assyrians at this point.

Tammaritu kissed the feet of my royal majesty and swept the ground with his beard. He took hold of the running board of my chariot and then handed himself over to do obeisance to me.

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640 (Inscription 11)

|

| Reconstructed street in Babylon |

On the ninth day of the intercalary month Ululu, Shamash-shuma-ukin mustered an army, marched to Cuthah and took the city. He defeated the army of Assyria and the Cutheans. He captured the statue of Nergal and took it to Babylon.

The Babylonian Shamash-shuma-ukin Chronicle

In 650 Bel-Harran, the governor of Tyre, was the Assyrian Limmu for the year. After the Kedarite Arabs under their king Iauta had joined the rebellion, Ashurbanipal launched a punitive expedition against them that seems to have had some success in burning the encampments of the Kedarites. He also instructed the king of Moab, Kamas-halta, to attack their western frontier, which also appears to have been relatively successful. It is interesting that he required the Moabites to do the fighting, as it would seem that most of the Assyrian troops in the west had been withdrawn to help in the war against Elam and Babylonia.

|

| Assyrian soldiers fighting Arabs and burning their tents |

Inscription of Ashurbanipal written around 640’s (Inscription 3)

While fighting continued on the Elamite frontier and in the deserts, the main Assyrian army closed in on Babylon itself and on the 11th day of the month of Du’uzu, the Assyrians began to besiege the city itself. Babylon was strong, but the Assyrian army was expert in siege craft and this was not a battle that they could afford to lose.

The eighteenth year: On the eleventh day of the month Du'ûzu the enemy invested Babylon.

The Babylonian Shamash-shuma-ukin Chronicle

|

| Ashurbanipal Lion Hunt Relief |

I try to end these blogs with a story and I realise that I have not yet talked in detail about the weird and wonderful story of Gyges. In a previous blog post I mentioned that he is the only person to my knowledge to be tangentially connected to the Book of Revelation, the Koran, Plato, Alexander the Great, the history of money, voyeurism, the One Ring of Sauron in Lord of the Rings and Conan the Barbarian. So how did this strange tale begin to grow around this man?

Gyges is supposed to have usurped the throne of Lydia around 717, which is far too early. If he was conspiring with Psammetichus in the 650’s this would give him an absurdly long reign. It is more likely that this event happened sometime around 680, but I am no expert in chronology so will leave this for the classicists to argue. He was a competent ruler remembered by the Greeks and Assyrians alike. The Assyrians spoke of him as a distant king who submitted to Ashurbanipal after having a vision in a dream before betraying Ashurbanipal and helping the Egyptian Saite Dynasty win independence. The Greeks remembered him as a rich tyrant usurper, who gave gifts to the Oracle at Delphi. Archilochus mentions him in his poetry and in later writings Herodotus mentions that he usurped the throne of King Candaules. In this story Gyges was the bodyguard of Candaules and Candaules wished to show him his wife naked, to show how beautiful she was. After the queen realised what happened, she persuaded Gyges to kill the king and take the throne. The act of displaying one’s lover naked to another is referred to as Candaulism, so this is the sex act that Gyges is connected to.

|

| Cuneiform tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal |

A stranger connection again to later culture may come from the Bible. In the book of Ezekiel, in chapters 38 and 39 there is a prince mentioned called Gog of the land Magog. This prince is unknown, but there is the possibility that it might be Gyges. While the names appear quite different to us, the Hebrew alphabet only recorded consonants. Gyges is the Greek way of saying the name. The original name was probably more along the lines of Guggu, which if only consonants are supplied and vowels are given later, might well be rendered as Gog. Other kingdoms are mentioned in the context, such as Meshech and Tubal, which could well be the kingdoms known to the Assyrians as Mushki and Tabal, which are both in Anatolia and in the same basic direction as Lydia. There are other arguments that would support this, including the list of descendants of Japheth given in Genesis. But it would take too long to go into here.

|

| German woodcut from 1544AD showing Gog and Magog |

Ezekiel 38:1-6

Why would a later prophet remember Gyges in such a manner, if it even is Gyges? This is a tricky question and one that has never been successfully answered. However, I believe that it has something to do with one of the other kingdoms mentioned in Ezekiel: Gomer. Gomer appears to be the Hebrew way of saying Cimmerian. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Remember that the vowels in Hebrew may or may not be correct. Remember also that the Greek language uses hard C sounds. So their word for Cimmerians was probably more akin to “Kimmeroi”. The Assyrian word for them is more like “Gimir”, which, with some vowel shifting is quite similar to the Hebrew “Gomer”. So, why does Gyges have a connection with the Cimmerians? In the Assyrian records he is a king who manages to stop these invading barbarians and defeats them, before they later turn the tables and kill him. However the Cimmerians under their leader Tugdamme (or Lygdamis in Greek, due to an earlier misspelling) also attacked the Greek cities of Asia Minor. It is possible that certain Ionian Greeks carried tales to the Levant of a far-away king who controlled and masterminded the movements of the barbarian hordes and that Ezekiel took this imagery and turned it into an archetypal picture of ravening hordes of invaders from the north.

If this is what happened, it worked. Gog ceased to be known as the King of Magog and instead became treated as a nation in the later Jewish and Christian writings, so that the phrase became “Gog and Magog”. These nations, tied into eschatological predictions of the end of the world, were treated as a shorthand for the gathering of the nations, enemies of the people of God, for a final battle at the end of the world. In the book of Revelations at the end of the Christian New Testament they are mustered by Satan after a thousand years and brought to a final battle against God, where they will be destroyed.

When the thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison and will go out to deceive the nations in the four corners of the earth—Gog and Magog—and to gather them for battle. In number they are like the sand on the seashore. They marched across the breadth of the earth and surrounded the camp of God’s people, the city he loves. But fire came down from heaven and devoured them.

Revelations 20:7-9

|

| Mughal painting showing Alexander walling off Gog and Magog |

Until, when he reached a pass between two mountains, he found beside them a people who could hardly understand his speech. They said, "O Dhul-Qarnayn, (Alexander) indeed Gog and Magog are great corrupters in the land. So may we assign for you an expenditure that you might make between us and them a barrier?" He said, "That in which my Lord has established me is better [than what you offer], but assist me with strength; I will make between you and them a dam. Bring me sheets of iron" - until, when he had leveled them between the two mountain walls, he said, "Blow with bellows," until when he had made it like fire, he said, "Bring me, that I may pour over it molten copper." So Gog and Magog were unable to pass over it, nor were they able to effect in it any penetration.

Surah 18:93-97

So this shows how Gyges is tangentially connected to the Book of Revelation, the Quran, Plato, Alexander the Great, the history of money, voyeurism, the One Ring of Sauron in Lord of the Rings but what of Conan the Barbarian? Well, in that film the titular hero is from a tribe of barbarians known as the Cimmerians, who with their connection to Gyges may have accidentally been tied into the archetype of Gog and Magog and the end of the world. This is only the very briefest introduction to this field of study, but it is a good starting point for further investigation.

|

| Map of the Near East around the late 700's |

The inscriptions of Esarhaddon

The inscriptions of Ashurbanipal

Letters from Babylonia and Assyria

Urartian Inscriptions

Herodotus’ Histories

The Adoption Stela of Nitocris

Secondary Sources:

On the conspiracy of Sasi

Some chronological sources (in German)

Related Blog Posts:

700-675BC in the Near East

Greece from 675-650BC

650-625BC in the Near East

No comments:

Post a Comment